Main menu

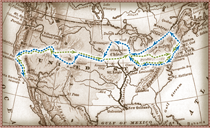

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Journey

- World Peace

- Stopping Racism in America

- Empowerment of Women

- More Principles...

- Prayer for America

The Light in the Lantern

BY ETHEL STEFANA STEVENS

Editor’s Note: — For seventy years a religion without church, priest, creed, or fixed form of worship has been spreading through the Orient, claiming converts and martyrs by thousands. Love and Unity are its sole principles; and on this broad program believers in various faiths can unite. This movement, called Bahá’ísm, has also extended to Europe, Great Britain, Hawaii, and the United States. In this country the Bahá’ís number thousands, with large assemblies in Boston, New York, Washington, Chicago, Los Angeles, Oakland, Seattle, and Kenosha, Wisconsin. The Mashrak-el-Askar (literally, the Dawning Place of Mention), a great temple where all races and creeds may worship, is about to be built in Chicago. Miss Steven’s thrilling story of Bahá’ísm in its years of persecution, and her sympathetic interpretation of the movement, gather an additional interest from the fact that the Bahá’í leader, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Abbas, is now making a visit to the Western world. Her acquaintance with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in his Oriental home makes her story authoritative — a first-hand, intimate study.

A YOUTH, green-turbaned and white-robed, knelt in the sun-baked execution place of Tabriz. Ringed about him stood the silent onlookers, row on row of sullen, swarthy faces under high caps of astrakhan. The executioner, baring his hairy arms, swung up his simitar for the blow. A groan ran through the ring of spectators, and the headsman momentarily faltered; then, like an arrow of light, his sword-blade whistled down. But it needed not the startled gasp of the onlookers to show him that it was the victim’s turban, and not his head, which rolled in Tabriz square. Recovering his poise, said the youth in purest Persian:

“Happy he whom Love’s intoxication

So hath overcome that scarce he knows

Whether at the foot of the Beloved

It be head or turban which he throws.”

Again the simitar swung upward, again it poised and turned and flashed, but this time the brightness of its steel was quenched in scarlet. One more recruit had gone on to join the martyr army of a religion for which, in the past seventy years, more than twenty thousand zealots have sacrificed their lives.

Its founder was a Persian youth of noble birth, who, in his native market-place of Shiraz, announced that he was The Báb, or Gate of Knowledge, whose coming Mohammed had foretold in that passage of the Koran which reads: “I am the City of Knowledge and Ali is its Gate.” It was a healthy enough doctrine which this young dreamer preached, for he proclaimed the advent of a purer religion than the degraded Mohammedanism that his people knew; he pleaded for a worthier conception of private religion and public duty; like a trumpet-call rang out his summons to throw off the priestly yoke. But always he spoke of one to come after him, to whom the divine truth should be confided in a fuller degree; one who would be a lantern to illumine not only the Persian nation, but the world.

That the preaching of such a doctrine promptly aroused the bitter hostility of the orthodox mollahs goes without saying, and attacks that had begun in jeering cynicism ended in fanatical persecution. But though his priestly enemies, with the whole weight of the state religion behind them, readily obtained an order from the government confining The Báb to his house and forbidding him to teach, doors and shutters could not restrict the new faith, which gained converts by leaps and bounds, among them a woman — a remarkable circumstance in the East — known as “Consolation of the Eyes” because of her surpassing loveliness.

When Nasr-ed-Din ascended the peacock throne, tolerance for the Bábis, as the members of the new faith were called, grew still fainter. The Báb was seized, and after two years of chains, darkness, and torture, according to the pleasant Eastern custom, he was shot in the market-place of Tabriz.

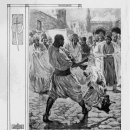

Comes on the stage, then, Bahá’u’lláh, who, while in exile with the Bábis in Bagdad, announced that he was the Knowledge of which The Báb had been but the Gate. Undiscouraged by their prophet’s tragic end, the Bábis’ acceptance of the new leader was prompt and joyous, the converts being known thenceforth as Bahá’ís or “Followers of Bahá.” Under the leadership of Bahá, the new religion spread among the credulous and fanatic Persians like fire in the autumn forest. Its startling increase in power so alarmed the government that when one member of the sect attempted to assassinate the Shah, there was an outburst of fanatical ferocity, whooped on by mollahs and officials, in which hundreds of Bahá’ís, among them the beautiful “Consolation of the Eyes,” were sent to join the goodly fellowship of martyrs by the various ghastly routes known to Eastern executioners.

Thenceforward the Bahá’ís were driven from pillar to post, being deported in turn from Bagdad to Constantinople, Adrianople, and finally to Acre, a fever-stricken penal colony on the Syrian littoral, where they were imprisoned for more than two-score years, and where Bahá’u’lláh died and is buried. Here, too, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, his eldest son, and the recognized head of the religion throughout the world, was trained to become the head of the movement.

This ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, or Abbas Effendi, as he is more generally known, is truly a remarkable man. That he is the greatest power for good among the two hundred millions of the Moslem world, there can be but little doubt. The success of his proselytism among people whose orthodox Mohammedanism is bred in bone has been absolutely astounding. Already he has converted to his creed a third of the Persian nation, and in Asia, Europe, America, all the world around those who revere him as the True Light are numbered by the tens of thousands.

But it has been no gentle path his feet have trod. For forty years, he and his handful of disciples were confined, by orders of Sultan Abd-ul-Hamid, as head of the Moslem religion, within the unhealthy confines of the convict-colony at Acre, tantalized always by the sight of Haifa’s cool white houses and the green slopes of Car-mel across the bay. Every indignity that his Turkish jailers could devise was heaped upon him, but still from every quarter of the Oriental and Occidental worlds the eager pilgrims came.

Some went back to sow on cultivated and receptive ground the seed which he had given them; while others, like the disciples of Galilee, went back to torture and to death. As the smoker of hashish becomes oblivious to pain, so do the followers of Bahá become intoxicated with a religious enthusiasm which makes them look death squarely in the eyes, and smilingly.

As recently as 1901, a band of Persian Bahá’ís, one hundred and seventy in all, died for their faith in the execution place of Yezd. One of them, a boy of fourteen, had been arrested with his father upon their return from a pilgrimage to Acre. Even the Persian officials were softened by the extreme youth and beauty of the lad. “You are too young to die,” said they, “and we will pardon you. Merely as a matter of form, curse the name of Bahá and you shall be set free.” But the boy refused point-blank, saying that he much preferred his faith to his life. (Does not the scene, with the calm childish face so bravely confronting those lean and thin-lipped mollahs, recall that other picture, in Rouen, five hundred years ago, when another child serenely faced her priestly persecutors and likewise refused to make a recantation?) So they signaled to the executioner, who cut the lad’s throat, according to the Persian custom, before the eyes of his father.

But in 1908 the body of the cruel Muzaffer-ed-Din, who had succeeded Nasr-ed-Din, as Shah, was borne by caravan across eight hundred miles of scorching desert, and laid beside his fathers in the great mosque at Kerbela the Holy; and, under the Russian protection which ensued, the persecutions of the Bahá’ís ceased. A few months later, that other evil old man, whom some called the Sick and others the Damned, was deposed from his unstable throne and imprisoned in a Salonikan villa. With the fall of Abd-ul-Hamid and the proclaiming of the Turkish constitution, Abbas Effendi and his disciples, with thousands of other political prisoners, were set free and, crossing the bay of Acre, took up their residence on the cool slopes of that sacred mountain toward which they had gazed so yearningly and so long.

Almost any afternoon you can see him for yourself if you will stroll in the streets of Haifa, that half-Syrian, half-Teutonic village, where ragged Turkish roustabouts load cargo from a pier which was built for the German emperor to land on, and where the shriek of the Mecca mail train echoes over the very slopes where once the Saviour trod. This servant of Bahá is a man with shrewd, kindly, courteous eyes that seem to look into you instead of at you, but that instinctively make you like them and all that goes with them. A keen, sun-tanned, friendly face framed as in silver by his long, white hair and beard; an expression that is alert, intelligent, and serene; a walk that is dignified without being conscious; a carriage that is peculiarly commanding. In him you see an Old Testament patriarch personified. Always he wears the snowy turban, the robe of plain white linen, and the gray wool overgarment peculiar to all Persians of high standing, while behind him, at the distance prescribed by respect, walks a group of his disciples with folded hands.

Regard him well, my friends, for in him you behold one of the most significant figures in the religious world to-day; one who is perhaps doing more for the uplifting of the Oriental than any other force; one who has actually suffered for his faith; one whom nearly two millions of people hold in greatest reverence as the Light in the Lantern, the Knowledge within the Gate.

Come with me now to the Master’s home in Haifa, that you may hear from his own lips the simple tenets of the Bahá faith. We shall have scant trouble in finding it, for every dragoman, cab-driver, and street urchin in the town will vociferously urge his services as guide to the residence of the Persian Prophet, as Abbas Effendi is locally called. The hour when the sun sinks behind the Samarian hills is his time for receiving visitors; and, however long and tiring his day’s work has been, he never refuses to admit and talk with those who have any just claim upon his time, though no Bahá’í would presume to visit Haifa without first obtaining his permission.

His white-walled, red-roofed, rose-smothered house, different in no respect from the dwellings of the Saviour’s day, is as simple within as without, for he lives, though wholly without affectation, in the utmost plainness. Leaving our shoes without the door, after the Oriental fashion, we enter a reception room, spacious, airy, and spotless, its woodwork and undecorated walls painted white, and the low divans that encircle it covered in unpretentious linen. It is a room with many windows, and jars of blushing roses stand on every table, for, as a result of his long imprisonment, perhaps, Abbas Effendi requires a wealth of light and flowers.

Just at sunset, the pilgrims and disciples enter with bent heads and folded hands and seat themselves silently about the room. For each man as he enters, Abbas Effendi has a kindly greeting, a tactful remark, a personal inquiry, or sometimes a humorous sally, which brings a flittering smile to the grave faces — for with these pilgrims this is a solemn and impressive moment. Most of them have suffered for their faith, and many of them have traveled far for this meeting with the Master.

This lean-faced convert at our right is a Fire-Worshipper from the shores of the Caspian; beyond him, he of the yellow skin and silken coat is a Sart from Samarkand; over there is a hungry-looking Parsee from the Punjab, and, in the corner, a keen-faced Japanese. And for each of them the Bahá has ready sympathy and sound, comprehensible advice. And therein lies his power. He possesses to a positively miraculous degree the faculty of interesting himself in every human soul that asks his spiritual or material aid, and it is this very power which has made him so passionately beloved by his disciples. But above all, he possesses that subtler quality of spirituality which is felt rather than understood by those with whom he comes in contact. Gentle, genial, and courteous always, he receives, instructs, advises, and assists with unfailing tact and understanding the cosmopolitan stream of pilgrims which flows so steadily and so increasingly toward this little Syrian coast town.

The charities of Abbas are bounded by no horizon of race or creed. The thirty-odd Persian families who followed Bahá’u’lláh into exile have more than once had his son to thank for the clothes they wore and for their daily bread. “Not a year passes,” a Roman Catholic remarked not long ago, “that Abbas Effendi does not help our work among the poor, and” — she paused, for his charities are never open — “if I were only permitted to tell you of the secret good that he has done!” Question them, and the imams of the Haifa mosques and the pastor of the German Lutheran Church, the foreign consular agents and the resident manager of the Hedjaz Railway, will tell you the same.

If you go to Damascus and walk in that street which is called Straight, you may perchance have dealings with a certain Persian youth, who, if he learns that your face is set for Haifa, will salaam profoundly and beg that you convey his respectful greetings and a letter to the Master. On that spring day in 1909 when the bloody wave of Kurdish fanaticism broke over Adana, leaving forty thousand corpses in its wake, he saw his shop pillaged and burned down, and his family butchered, and he himself was left for dead under a heap of slain. It was Abbas Effendi, hearing of his sad case, who sent him monetary help, started him in business afresh, and wrote him kindly letters that gave him courage to face life again. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá takes a personal interest in every one of the Persians in Haifa, helping to educate them when they are unable to afford education for themselves, settling their quarrels, deciding their differences, and advising them in their material as well as their spiritual wants.

Religion aside, is it any wonder that a man with such sympathy for humanity has gained the blind faith and devotion of his people?

The Effendi himself, as I have said, lives in the utmost simplicity. His own bedroom is almost Spartan in its plainness. A bowl of soup and a dish of rice usually compose his heartiest meal, which is invariably concluded by the ceremonial washing of face and hands in water poured over them by a servant, according to the Eastern fashion. In deference to Turkish prejudice, his wife and three daughters still shroud themselves, when out-of-doors, in the black feridjeh, or hooded mantle, which covers them completely, the veil or tcharchaff, falling like a curtain before their faces. Though his only son lies buried in the little white-walled cemetery outside of Acre, Abbas Effendi has never taken a second wife, as Persian custom would permit, for he holds that one marriage only, during life, is the highest conception of matrimony.

The lives of his womenfolk are not idle, for from early morning till late evening their services are required for the entertainment of many, and ofttimes distinguished, guests; as interpreters, should foreigners be among the visitors, for they are all accomplished linguists; and for the superintendence of a very busy and irregular household. Oriental hospitality is a duty, but when the visitors are as numerous and frequent as they are at Abbas Effendi’s house, it becomes a duty not without burdens.

“We never know how many people to prepare for when ordering a meal,” the daughters will tell you smilingly, “and we have to be ready for any emergency. Sometimes, when a number of pilgrims arrive, we have as many as twenty unexpected guests at our evening meal.”

“Love One Another” might well be the watchword of the Bahá faith. Love, Abbas Effendi will tell you, is the beginning and end of all. With love triumphant, all disputes, racial or religious, political or personal, will disappear like darkness before the dawn. God has revealed His light many times in order to illumine for mankind the path which leads to the gateway of the true religion. Buddha, Confucius, Zoroaster, Moses, Christ, Mohammed, Bahá’u’lláh, were all gateways to a common garden of Love; all lanterns in which the Light of Truth was placed. A humanity bound together by sympathy and unselfishness; a world in which there is neither intolerance nor war; a universal religion with but two essentials: love for man and love for God; a universal language and a universal educational system — such, in a nutshell, is the Bahá creed.

It is on the road to a practical realization of such an ideal that Abbas Effendi is setting the feet of his people. That his theories have worked out among those who follow him is evidenced by the dozen nationalities which often sit down at his table in utmost harmony; and this, remember, in a land where religion and fanaticism are all but synonymous; where a true believer will rarely consent to use the dishes that an infidel has handled, much less consent to eat beside him. The Effendi is a keen and clever controversialist; his verbal parries and thrusts are quick as rapier-strokes, as has been learned to their discomfiture by theologians of all creeds who have visited Haifa for the sole purpose of confuting him with their arguments. So highly is he respected, even among the most bigoted followers of Islam, that many Moslem ecclesiastics of note have stopped at Haifa to pay him a visit of ceremony on their way to the Holy Cities.

Nor does he confine himself to things spiritual and theoretical. He takes a lively interest in those political, social, and educational movements of the Western world which he holds to be the beginning of the fulfilment of the prophecies of Bahá’u’lláh. With equal facility he discusses Esperanto, which may be destined, he says, to become the universal language predicted by his predecessors; the efforts of the peace conferences toward the abolition of war; and the great philanthropies of Europe and the United States. He speaks confidently of the day when chauvinism, that attempt to further the interests of one nation at the expense of another, which so often passes for legitimate patriotism, will be replaced by a wish to further the interests of humanity at large; of a time when a universal language will be taught in schools founded on an international educational system which shall have no religious bias, no racial bias, no political bias; of an era in the not far-distant future when the genius of inventors, instead of being directed toward the construction of engines of war and methods of destruction, will be exclusively devoted to the alleviation of mankind’s miseries. He discusses, too, the scientific questions of the day, displaying as remarkable a familiarity with the discoveries of Curie, Edison, and Peary as with creeds, dogmas, and beliefs.

And this versatility, this capacity to reason and form suggestive theories on any subject, is all the more amazing when one remembers that Abbas Effendi, exiled to Bagdad with his father before he was six, and for forty years a jealously guarded prisoner at Acre, where he was wholly cut off from the world of culture, has never known a single year of schooling.

Along with his mental grasp and power, he has that inestimable gift of humor which brings priest, peasant, and prince on to a ground of common understanding. Always he clings to the Oriental habit of illustrating his teaching with stories, which are ofttimes of a delightfully ironical and amusing nature. As I sat with him one day in his garden, where the climbing crimson roses stood out like splotches of blood against the stucco wall, some turn in the conversation led us to a discussion of the ignorance and superstition of the Mohammedan officials. “I remember one day when I was calling on the Mutessarif of Acre,” said Abbas, his eyes twinkling at the humor of the recollection, “a madman suddenly burst into the garden where we were all seated. Every one rose to his feet as soon as the man’s insanity was realized — the Mutessarif even insisting that he should take the seat of honor; for the Moslems, you know, regard madmen as sacred, and their utterances as directly inspired by Allah. Scarcely had the customary coffee been served when a mongrel street dog strayed in through the gate, which the madman had left open, and began to bark at the company.

“‘Pray tell us, Effendi,’ said the Mutessarif to the madman, with great respect, ‘what the dog is saying.’

“‘I don’t know what the dog is saying,’ said the lunatic.

“‘But surely the Effendi understands the language of dogs,’ insisted the Mutessarif, who was a Kurd. ‘I’am certain that if you wished you could translate for us what the dog is saying.’

“Quick as a flash the madman turned on his Kurdish questioner. ‘Who told you that I could speak Kurdish, Excellency?’ said he.”

The philosophy of Abbas is essentially human, in the highest and broadest sense of the word, for he calls the attention of humanity not to the letter, but to the spirit, of religion. Having in mind the self-imposed deprivations of the monastic and the self-inflicted punishments of the dervish orders, I asked him one day whether, in his opinion, the crushing of the desires and needs of the flesh helped the soul to attain a spiritual state. “Asceticism is not necessary,” he replied. “A soul grows by the exercise of human virtues, by the observance of human morals, and by divine favor. The extreme asceticism of the saints was only a form of superstition. The monasticism of the Christian Church was mistaken. St. Paul was responsible for much of this, for in one of his epistles he praised those who do not marry and prophesied that sects would arise, the members of which would practise celibacy. St. Paul disapproved of marriage; but God did not give us good gifts that we should spurn them. He created these forms of happiness that His people might bless Him.”

Abbas Effendi denounces superstition and deprecates popular interest in miraculous phenomena as tending to divert the mind from the pursuit of real and practical religion. His eldest daughter once said to me: “We Bahá’ís do not dwell upon the miraculous. A man wrote a book in which he enumerated the miracles of The Báb. Bahá’u’lláh promptly burned it lest it should prove a cause for later superstition. He even forbade his followers to talk about miracles, for he held that they tend to lower a religion and divert the thoughts of people to relatively unimportant things. Which is the more important, pray — the miracles or the life of Christ? And yet, because people have not been able to believe these miracles, they have doubted Christ’s teachings.”

The Bahá’í faith is unique in that it has no churches, no priests, and no fixed order of prayers. Every man is his own priest and is responsible for the growth of his own soul. It is true that Bahá’u’lláh once wrote a book of prayers designed to fit the various needs which might arise, but no Bahá’í is obliged to use them. I asked Abbas Effendi if he considered prayer to be necessary, since God presumably knows, without being told, the wishes of all hearts. “If one friend loves another, is it not natural that he should wish to say so?” he replied. “Though he knows that that friend is aware of his love, does he still not wish to tell him of it? If there is any one whom you love, do you not seize all opportunities to converse with him, to write him, to bring him gifts? If you felt no such desires, it would be a sign that you did not love your friend. It is true that God knows the wishes of all hearts; but the impulse to pray is a natural one, springing from man’s love for God.

“If there be no love, if you can find no pleasure or spiritual enjoyment in prayer, do not pray. Prayer should spring from love, from the desire of the person to communicate with God. Just as a lover can never talk enough with his beloved, so does the lover of God wish always for constant communication with the Deity. Prayer need not be in words, but rather in thought and action. But if this love and this desire are lacking, it is useless to try to force them. Words without love mean nothing. If a person talks to you as an unpleasant duty, finding neither love nor enjoyment in the meeting, do you wish to converse with him? So God regards those who pray to Him merely from a sense of duty. Learn to love Him first, and the prayers will take care of themselves.”

“But how is this love to be cultivated?” I inquired. “How is a love for God to be obtained? There are many people who admit the existence of a Deity, but without feeling any emotion.”

“Knowledge will bring love,” said the Effendi. “Study, think, reason, try to comprehend the wisdom and the greatness of God. The soil must be fertilized before the seed is sown. When once you appreciate what He has done, you can not fail to love Him.”

On another occasion, speaking of love, that watchword of the Bahá’í faith, he said:

“Love is unity, and unity is love. It unites in friendship the people of every race and every creed. Love in its highest form has no thought of the personal advantage which it may gain from the one who is beloved. If you love truly, your love for your friend will continue even though he should ill-treat you. A man who really loves God will not let sadness or illness or misfortune weaken his love for Him. You do not love God because He created you — for your life may be filled with miseries and dissatisfactions. You do not love God because He has given you health and wealth, for these may disappear at any moment. You do not love God because He has given you the strength of youth, for old age will surely come upon you. No, you love Him not for these outward manifestations, but because of His perfections and because He is perfection. A moth loves the light, and, though its wings are singed, it throws itself against the flame. It does not love the light because it has conferred some benefit upon it, but because it is the light. So the true lover of God loves Him for Himself alone, not for what he can obtain from Him.”

It is this mystical fervor, these high spiritual ideas, which constitute the real life of Bahá’ísm. “When true knowledge begins, earthly knowledge drops away,” a Bahá’í said to me one day, speaking with some amazement of the habit which many of the Europeans who visit the Effendi have of asking purely psychological questions. To the Bahá’í mind such questions are unnecessary and futile. To endeavor to explain the riddle of the universe by any philosophical theory seems to them absurd. The spiritual life, once entered upon, is beyond reason, for Bahá’u’lláh wrote:

When the fire of love is become ablaze

The harvest of reason will be wholly consumed.

The aim of the Bahá’ís, briefly put, is to establish an earthly kingdom of Love; a kingdom whose only law shall be the Golden Rule. “The religionists of the world,” Abbas Effendi remarked one day, “have abandoned the essence of their faiths and hold only to the letter. Picture the students in a university wrangling and disputing with each other as to which professor was the best, instead of attending to the lessons given them by those professors, and you have a parallel of the conditions which prevail in the world to-day. The religious conceptions of every creed presume the existence of a medium between God and man. The spiritual teachings of these divine mediums, whether Hebrew, Moslem, or Christian, have been essentially alike; the Word of God, whether transmitted by Moses, Christ, or Mohammed, is the same. Moses, Christ, Mohammed — what, after all, are these but names? And what do names, mere words, matter? Yet people quarrel and even kill each other over these names. The true object of religion, the real goal of spiritual progress, is to make every soul reflect the divine. Each soul must become as radiant as a lamp.

“Such, then, is our message and our mission. Day and night we must labor to establish community, unity, and harmony among mankind. The world has had enough and to spare of quarrels, backbitings, and criticisms. See how the Catholics disparage the Protestants and the Protestants the Catholics, and both of them the Jews. See how, here in this Syrian land, the adherents of Moses, Christ, and Mohammed are always at each other’s throat. Do the Catholics and the Protestants, Christians both, love each other as Christ commanded? Have they a brotherly feeling toward each other? And as it is with one religion, so it is with all. But we Bahá’ís hope that these obstacles to a mutual love and understanding may eventually be removed; that the followers of each belief may respect and admire the others; until the Word of God, with all its perfections, brings them all unto His kingdom.”

“What is the true definition, Effendi,” I asked, “of a Bahá’í?”

Standing there in his spotless robes, amid the mingled fragrances of his quiet garden, on his kind old face the serenity which comes only from faith and love, he made an answer which I like to remember. “To be a Bahá’í,” he said, “means to love humanity and try to serve it; to work for the universal peace and the universal brotherhood of mankind.”

No pilgrim departs from Haifa without first paying a visit of respect to the little house in Acre where Bahá’u’lláh lived and taught during his years of exile, and to the tomb where he lies buried. With your permission we too will go, for the ten-mile journey is not arduous, and the surroundings amid which Bahá’u’lláh spent so many years are strikingly significant of the simple faith of which he was the Light. From the historic slopes of Carmel our way lies northward, the dusty road, yellow as brass under the tropic sun, bordering the cobalt bay. It is a lumbering vehicle, with amazingly high wheels, in which we travel, for on the journey two rivers must be forded — the Kishon, from which Elijah took water to pour over his sacrifice, and the Namein.

Acre, unlike its sister town across the bay, is purely Oriental; its gloomy, vaulted streets, its palm-shaded mosques with their slender minarets, whence the muezzin, the church-bell of the East, calls the faithful to prayer, and the caravans of supercilious camels pad-padding their haughty way through the dim and clamorous streets, give no single reminder of those Crusaders who made the name of Acre a synonym for valor throughout medieval Christendom. The once carefully tended forecourt of the house where Bahá’u’lláh lived has been trampled ruthlessly by lawless Arabs; but, within, the little garden is still sweet with flowers, weeded and watered by the few Persians who now tend the place, since Abbas Effendi and his family have removed to Haifa. One of them, a venerable, smiling man in Persian robes and a spotless turban, was, he told me, a contemporary of Bahá’u’lláh.

Afterward I learned his story. Tortured and imprisoned for more than fourteen years at the time of the persecutions, he never wavered in his faith. On one occasion, when he was being transferred from one prison to another, many days’ journey away, he and his fellow-prisoner, another Bahá’í, were lashed to the backs of donkeys, heads downward, and in this excruciating posture were carried day after day under the desert sun. But always Haidar Ali laughed and sang, and the more he sang the more his captors laid the thongs of their kourbashes on him, asking, “Now will you sing, dog of an unbeliever?” But he answered that the floggings only increased his happiness, since they gave him the satisfaction of enduring something more for the sake of God.

I asked Haidar Ali if he always smiled. “For you Bahá’ís all look happy,” I added.

“Sometimes we have surface troubles,” said he, “but they can not touch our happiness. The hearts of those who belong to the Malakut [kingdom of God] are like the sea: when the wind is rough it troubles the surface of the water, but a fathom down there is perfect calm and clearness.”

When the Bahá’í converts were first exiled to Acre, the entire seventy of them were closely confined in an ordinary Turkish house, with two barred rooms. This is visited by pilgrims; but it is rather the Rizwan, or Garden of God, in the outskirts of the town, which is most intimately connected with Bahá’u’lláh’s life and teachings. Bahá’u’lláh suffered greatly from his long confinement, so his followers, as soon as a relaxation of its rigors permitted, put their scanty savings together and bought a piece of land without the walls at Acre, where with their own hands they made him a wonderful garden. In this exquisite spot the Bahá did his teaching. The Rizwan lies at the parting of the Namein, so that on either side of it the river flows. It is filled with every imaginable kind of flower; the bees and the butterflies run riot in it; and the prodigal Oriental springtime fills the air with a hundred perfumes.

On one side a little square, paved with pebbles in designs of black and white, has steps leading down to the river, while in the center the water from a flower-concealed fountain splashes into a shallow marble conduit which conducts it by devious ways into the river, with a gentle and cooling sound. In this square grow two great mulberry trees, and beneath them are wide benches and a wooden table, painted blue and white and stained by sun and wind. In summer, so thick is the foliage of these trees and so wide their spreading branches, that the little square is like a green tent, within the cool recesses of which Bahá’u’lláh talked with his disciples and taught and studied. Here, too, he used to write on summer evenings, by the light of a big lantern suspended in the overhanging branches, and ever since, in this same lantern, the gardeners are wont at nightfall to place a candle, in memory of him whom they call the Greatest of Lights.

Around the tomb of the great teacher has been made another garden, the most beautiful of them all. Inside a covered courtyard is the prophet’s tomb, silent and very sunny. The light filters in through delicately veiled windows, and the square of carpet which covers that portion of the floor beneath which the body has been laid, is of a tender green. Above the tomb, in Persian script, is the simple inscription: “Bahá,” and lamps and candles and flowers are everywhere. There are no symbols of grief such as we of the West associate with death; no sad funereal trappings. It is a silent room in an empty house — and nothing more.

I have shown you now, as best I am able, what manner of man is this Abbas Effendi who is variously held to be impostor, priest, and prophet. Whether he deserves the title of prophet I do not know; no one knows; that, the future alone can tell. That he is a good man and sincere, there can be no doubt. That the faith which he holds and the creed which he preaches might be followed with benefit by us all, there is no gainsaying. Be you Confucian, Buddhist, Zoroastrian, Christian, Moslem, or Jew, to follow the lantern which Abbas lights can bring you to no harm; to abide by his Rule of Love can be no heresy. He preaches a clean and wholesome creed, and though you may question the divine origin of his mission, there is no denying that he is a sincere, courageous man, a figure whose increasing influence is already world-wide in its significance.

[picture caption: HAIFA, THE HOME OF ABBAS EFFENDI. Drawing by Neal A. Truslow.]

[picture caption: ABD-UL-BAHA, ABBAS EFFENDI, THE HEAD OF THE BAHAI FAITH. Drawing by William Oberhardt from a photograph. Copyright by the Pictorial News Co.]

[picture caption: THERE WAS AN OUTBURST OF FANATICAL FEROCITY, WHOOPED ON BY MOLLAHS AND OFFICIALS, IN WHICH HUNDREDS OF BAHAIS WERE SENT TO JOIN THE FELLOWSHIP OF MARTYRS.]

[picture caption: MIRZA ASAD ULLAH; ONE OF THE BAHAI TEACHERS WHO CAME FROM PERSIA TO SHARE THE EXILE OF HIS BELOVED MASTER, BAHA ULLAH. Drawing by William Oberhardt.]

[picture caption: THE STAIRS LEADING TO ABD-UL-BAHA ABBAS’S ROOM IN HIS HOUSE AT ACRE. Drawing by Neal A. Truslow.]