Main menu

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Journey

- World Peace

- Stopping Racism in America

- Empowerment of Women

- More Principles...

- Prayer for America

The Significance of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Journey across America

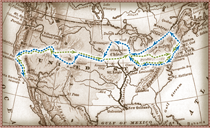

One hundred years ago there occurred an event of unparalleled, though, until now, generally unrecognized, significance to the destiny of America. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Son of Bahá’u’lláh, the Prophet-Founder of the Bahá’í Faith, arrived in New York on April 11, 1912. His sojourn in North America lasted 239 days, including ten days in Canada, during which He traveled to important cities from the east to the west coast and met with people of divers backgrounds and interests. No other figure of comparable stature or imbued with the singular purpose that impelled Him has so favored this country.

By the time of His arrival, 19 years had elapsed since, by fortuitous circumstances not involving any Bahá’í, the name of Bahá’u’lláh was publicly mentioned for the first time in the Western Hemisphere. It happened in Chicago on September 23, 1893, almost a year and a half after the ascension of Bahá’u’lláh, at the World’s Parliament of Religions which was connected with the Columbian Exposition commemorating the four hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America. Thus began the first episode in the history of the Bahá’í Faith in America. By February 1894, a Syrian doctor who had accepted the Faith in Cairo arrived in Chicago and began a vigorous effort to teach the new religion. Within two years hundreds professed their belief in it; additional conversions took place in other major cities to which he traveled. The laying of the foundation of the American Bahá’í community had begun. The enthusiastic members of the newly born community lost no time in initiating correspondence with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá while He was still a religious prisoner in the fortress at Akka in Ottoman Palestine.

These developments must have delighted and gratified ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, but could hardly have been wholly unexpected by Him. Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith appointed by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as His successor, indicates that in 1893, sometime before the Chicago happenings, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had revealed a verse that had “already foreshadowed” His Western journey, “an auspicious event which posterity would recognize as one of the greatest triumphs of His ministry, which in the end would confer an inestimable blessing upon the Western world.” It was with this great expectation inspired by the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, that He, Who had for fifty years been subjected to imprisonment and exile for His religion, undertook, at the age of 68, the long journey from the Holy Land to the Western world.

“The Day of the Promise is come,” Bahá’u’lláh declares in announcing His mission as the Promised One of all religions, and as the One whom the Báb, His Forerunner, said, God would make manifest. In countless verses Bahá’u’lláh acclaims the potencies with which His Revelation has infused the life of the planet. “The oneness of mankind” is the central theme and ultimate goal of His teachings; hence, He repeatedly calls for the world’s peoples to establish unity among themselves, warning that there is no alternative if the human race is to fulfill its purpose for being. The insistence of this call implies the coming of age of the entire human race—the highest level to which humanity can evolve after untold ages of social development involving the prolonged stages of its collective experience. An organic global unity—a Golden Age of peace as promised in all the Holy Scriptures—is the consummate stage to which Bahá’u’lláh directs humanity. This pivotal theme was elucidated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in His numerous addresses to American audiences in a variety of settings.

In Cleveland, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá uttered these potent words in the opening sentences of one of His many public addresses: “The American continent gives signs and evidences of very great advancement; its future is even more promising, for its influence and illumination are far-reaching, and it will lead all nations spiritually.” He then discussed the prerequisite for the fulfillment of so astonishing a prediction. While acknowledging the necessity of material progress in America, He likened a “material civilization” to a body, “whereas divine civilization is the spirit in that body.” Hence, He hoped that the American people, recognizing this reality, “may attain both material and spiritual progress.” Shoghi Effendi explains that the repeated comments of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá concerning America’s future are indications of the potencies released by the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, which will eventually impel the American people and government to take initiatives that will lead ultimately toward a global political union similar in its characteristics to the federal union of the United States.

For the Bahá’ís His visit was particularly distinguished by certain symbolic acts, which by the examples He set invested their nascent community with certitude. With His own hands He laid the cornerstone of the Bahá’í House of Worship on the shores of Lake Michigan near Chicago, the first such Bahá’í institution in the West, which He designated the “Mother Temple.” He united in wedlock two Bahá’ís from different nationalities and ethnicities, one white, the other black, in a bold demonstration of the profundity of the Bahá’í principle calling for the elimination of racial prejudice. Years later, at His insistence, the first race unity conference was held in the nation’s capital. To promote the equality of the sexes, a cardinal principle of the Bahá’í Faith not taught in the scriptures or laws of other world religions, He frankly appealed on various occasions for the rights of women to be recognized.

But even more outstanding than these and other such acts was His “dynamic affirmation” in New York of the Covenant instituted by Bahá’u’lláh to secure the unity of the Bahá’í Faith and eventually to actualize the unity and permanent peace of the world—a Covenant of which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was the appointed Center. On that same occasion, He designated New York the “City of the Covenant.” The placing in this city several decades later of the headquarters of the United Nations, where representatives of all countries continue to meet, curiously suggests a probable relevance to that designation.

A commentator on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s travels in the West has written that Beyond the words spoken there was something indescribable in His personality that impressed profoundly all who came into His presence. “Beyond the words spoken there was something indescribable in His personality that impressed profoundly all who came into His presence.” Similar observations were noted in newspaper articles appearing in places where people attributed to Him the characteristics of a Prophet and even, in individual instances, wrongly regarded Him as Christ returned. He was repeatedly quoted in the press denying that he was a prophet. It is indeed difficult to describe One possessed of so magnetic a personality or to attempt to assess the effects, wherever He went, of His encounter with so many people, whether of high or low estate. It is a mystery that appears to be inherent in the incomparable office of Center of the Covenant. He was no Prophet or Manifestation of God, as He Himself made emphatically clear. But He occupied a station that qualified Him as the perfect exemplar of the Bahá’í teachings and made Him, together with Bahá’u’lláh and the Báb, one of the Three Central Figures of the Faith. Thus, in His person, Shoghi Effendi explains, “the incompatible characteristics of a human nature and superhuman knowledge and perfection have been blended and are completely harmonized.” He, “in the entire field of religious history, fulfills a unique function.” It is in this exceptional context that His activities in America must be contemplated and understood.

Two documents revealed by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá are especially notable, for they are indispensable to the existence of the Faith itself and to its world-shaping influence: The Tablets of the Divine Plan, constituting the charter for the global expansion of the Faith, which He addressed to the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada; and His Will and Testament, the charter of an administrative system, which is regarded, as Shoghi Effendi states, “not only as the nucleus but the very pattern of the New World Order destined to embrace in the fullness of time the whole of mankind.” It was in America that the initiatives were taken to execute these two mandates, making the American Bahá’í community, with the collaboration of its ally, the Canadian Bahá’í community, both the primary mover of a systematic global teaching plan and the “cradle” of the Bahá’í Administrative Order.

In retrospect, these two iconic legacies of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the seminal actions they inspired cast an awesome light on the meaning of His activities in North America. It is no wonder, then, that He, as Shoghi Effendi reports, “intimated that the establishment of His Father’s Faith in the American continent ranked as the most outstanding among the three-fold aims which, as He conceived it, constituted the principal objectives of His ministry.”

Time doubtless will prove ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to the United States as having been a defining event in the country’s history, for it bestirred the spiritual potencies so vital to the realization of its preeminent, providentially ordained role in the ultimate ordering of world affairs—a prospect so sublime, so much greater than the scope which could have been apparent to America’s Founding Fathers, however glorious the hopes they had entertained for this uniquely conceived nation.