Main menu

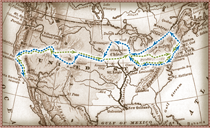

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Journey

- World Peace

- Stopping Racism in America

- Empowerment of Women

- More Principles...

- Prayer for America

Ways of the World

‘ABDU’L-BAHA: The Prophet Tells of the Spiritual Growth of the Movement Which Calls Upon Humanity to Put Aside Differences and to Achieve Unity.

by JOHN D. BARRY

WHEN I called to see ‘Abdu’l-Bahá for the second time I again found the house in California street filled with people. In a few moments I was told that the master was ready to talk. He was sitting in the same place, on the couch near the window, a gray robe flowing down from his shoulders over his thick-set figure, his thin gray hair falling behind his neck, his gray beard partly hiding his aged face. He explained that he had not been feeling very well. He had not as yet become adjusted to the California climate. But he spoke with his characteristic vigor and authority.

Our talk turned to the spiritual development of the Bahá’í movement. As ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke, his words would be translated by that quiet and courteous interpreter.

“Our movement goes back to the young leader who called himself The Gate or The Door, in our language, The Báb. He said: ‘I have the feeling that I am the gate to an invisible personage. Whosoever desires to communicate with that personage must need go through this gate.’ Báb had an inner effulgence. He began his career as prophet at twenty-five. He worked for seven years. Then he was put to death. It was claimed by the ecclesiastical authorities of Persia that his teachings were harmful. They anathematized him on account of his books. They said: ‘This person is a source of misguidance to the nation. His existence will destroy the reigning monarchy.’ Though his followers were bitterly prosecuted, they rapidly multiplied. In all his books His Holiness, The Báb, proclaimed the glories of the person that was coming. He was like John the Baptist. He said: ‘That which you have inflicted upon me I forgive. But beware lest you disobey Him whom God will manifest. Beware lest my books be used as pretexts of denying him.’ At the time prophesied The Bahá’u’lláh appeared. He was then forty-five years old.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke with reverence. He said nothing with regard to his being the son of Bahá’u’lláh. When I asked him to give me some details of his father’s early life he seemed to hesitate. He evidently regarded my question as unimportant. But I was curious to know what the forces were in the life of Bahá’u’lláh that made him believe he was the prophet foretold of Báb. “Long before he revealed himself Bahá’u’lláh knew that he was the destined one. But he kept silent. He was a man of great wealth and of wonderful natural gifts. As a boy he went to no school. But his power was such that he was recognized as a great figure.”

“Did he have any personal relations with Báb?” I asked.

“The two never met. But at the age of thirty-two Bahá’u’lláh received a tablet from Báb, saying that he was the one prophesied. Of the two Bahá’u’lláh was by far the greater. Some of the teachings of Báb he discarded. For example, Báb said: ‘War is good.’ Yes, he advocated war. He praised conquest. Bahá’u’lláh declared that war was contrary to the oneness of humanity. Báb considered that all scientific books should be burned. But ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had no such belief.”

“What did Bahá’u’lláh do after he revealed himself?”

“The first thing he did was to write an epistle to all the kings of the earth and to the pope and to your President, then U.S. Grant, proclaiming the brotherhood of man and the importance of international peace. Soon the followers of the Báb, who had been dwindling away, came and others joined the movement. The government then strove against Bahá’u’lláh; they banished him to Baghdad, and then to Constantinople and then to Roumania. In spite of all this tyranny the apostles went abroad and spread the word. At last the authorities imprisoned Bahá’u’lláh in the Fortress of Akka, in Syria. Even in prison, while under surveillance, he was able to promulgate his teachings and to write his messages to the world.”

I should have been glad to hear from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá of his own early experience in taking up the work left by his father. But the interpreter explained that he disliked talking about himself. Perhaps, too, it would have been a painful history to discuss. For, as I knew, it included long years of imprisonment for the sake of the faith. But it was plain that this experience, instead of harming, had given the teacher a greater spirituality.

During our talk figures had been hovering about the door, one of them busily writing. Word came that the house was crowded with visitors, all anxious to secure an interview. The ‘Abdu’l-Bahá announced that he would go down and speak. They should all be invited into one room. In a few moments the drawing room on the ground floor was crowded. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá entered, walking vigorously. At once he began to speak of the message of the new faith. It came not to destroy or to disrupt, but to create in mankind universal harmony. In Persia the members of the faith had suffered great trials; but they were strong in their devotion. From far away they sent loving remembrances, inviting the East and the West to shake hands. It was folly for mankind to contend on account of thoughts and feelings. Such things were in the hands of God. Mankind must learn to control nature and to become identified with the spirit. As the speaker went on he grew more and more metaphysical and rhapsodical. His words, repeated by the interpreter, assumed quaint English form. When he had finished he turned and strode into the hall and up the stairs.