Main menu

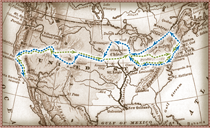

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Journey

- World Peace

- Stopping Racism in America

- Empowerment of Women

- More Principles...

- Prayer for America

Ending Extremes of Poverty and Wealth

On the eve of ‘Abdu’l-Bahás journey across America, a new industrial order had emerged, creating nationwide prosperity, but also exacerbating crushing poverty and inequity. Publishers and industrialists grew very wealthy providing newspapers, magazines, automobiles and steel, building the railroads that crisscrossed the U.S. and the ships that transported American manufactured goods to Europe. In the midst of such vast wealth, the poor languished in crowded and often disease-ridden urban housing. The first decades of the 20th century saw huge numbers of children working in mines, glass factories, textiles, agriculture, canneries, and as newsboys, messengers, bootblacks, and peddlers. In 1904, the National Child Labor Committee was formed and a national child labor reform campaign began, but a law to actually prevent child labor would not be passed by Congress until the mid 1930s.

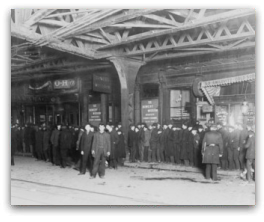

The year 1912 saw America with a population of 92 million, with a low 2% unemployment rate, but the chasm between the wealthy and the poor was impassible. Workplaces were profoundly unsafe. On the railroads alone, between 1890 and 1917, 72,000 workers were killed and more than 2 million injured. In addition, there was no social safety net—worker’s compensation was a new idea, passed by just 10 states by 1911. Neither Social Security, Medicare, nor Aid to Families with Dependent Children existed—so the elderly, widows, orphans and the ill were left to their own devices, meager as they were. Partly due to these social disparities, worsened by poor sanitation and a lack of good public health practices, U.S. life expectancy was on average just 48 years for men and 52 years for women.

Labor unions grew in size and influence as the middle classes became more unhappy and restless with the status quo. Poverty was on the rise, industrial monopolies continued to increase despite the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, safety for workers in the workplace was largely dismissed as irrelevant, and children were in the workplace in their thousands. Nearly 20% of urban children were undernourished and only one-third were enrolled in elementary school. Immigrants had flooded the cities, many—including Poles, Finns from Russia, and Macedonians and Bulgarians from Turkey—fleeing political or religious oppression. Others, like the Irish, fled famine and poverty, swelling the ranks of the poor.

Social reforms in the 1940s took the first small steps to redress these inequities through the Social Security system, whereby the aged would receive an income set aside from their earnings, and the poor would receive medical care. The U.S. GI bill after World War II enabled thousands of returning military men and women to obtain college degrees and rise to serve their countries in all the professions.

Mingling with America’s Rich and Poor

Into this milieu of U.S. income disparity stepped ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Garbed in His simple abba, He dined with society’s elite, resided in stately homes, and was feted at elegant luncheons and dinners. Yet He consistently reminded the rich of their responsibility to the poor in their midst, and called for them to voluntarily support the disadvantaged who lived all around them. At a private home on the fashionable Upper West Side of New York City, He admonished his audience:

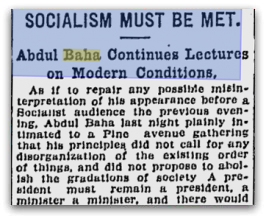

“Each one of you must have great consideration for the poor and render them assistance. Organize in an effort to help them and prevent increase of poverty. … [T]he laws of the community will be so framed and enacted that it will not be possible for a few to be millionaires and many destitute. One of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings is the adjustment of means of livelihood in human society. Under this adjustment there can be no extremes in human conditions as regards wealth and sustenance. For the community needs financier, farmer, merchant and laborer just as an army must be composed of commander, officers and privates. All cannot be commanders; all cannot be officers or privates. Each in his station in the social fabric must be competent — each in his function according to ability but with justness of opportunity for all.”Teaching by Example

Wherever ‘Abdu’l-Bahá went, He demonstrated by His example and His words that both extremes—extreme wealth and extreme poverty—must be eliminated if human civilization were to progress.

By His example, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá eschewed every hint of pomp or pretense. While in New York, He received dozens of poor Bowery children to visit Him at the elegant home where He was residing. As the rowdy boys crowded into His room, He greeted each with a warm handclasp or a friendly hand on a shoulder, all with smiles and laughter. On another occasion, He greeted a soot-covered man who had ridden the rails across country to New York see ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. He welcomed the grimy traveler into His room in that same posh Upper West Side house, greeting him with a kiss to his soot-blackened cap.

Spiritual Solution to Economic Problems

‘Abdu’l-Bahá in 1912 foresaw that humanity’s gradual spiritual maturation would lead to a future of economic equity and justice for all strata of society. He also advocated a spirit of voluntary giving, in addition to a progressive tax system. He said:

“[A]ll mankind will find comfort and enjoyment in life. It is not meant that all will be equal, for inequality in degree and capacity is a property of nature. Necessarily there will be rich people and also those who will be in want of their livelihood, but in the aggregate community there will be equalization and readjustment of values and interests. In the future there will be no very rich nor extremely poor… The significance of it is that the glad tidings of great joy revealed in the promises of the Holy Books will be fulfilled. Await ye this consummation.”Today, at the United Nations and other fora, Bahá’ís are contributing to the discourse on how to moderate extremes of wealth and poverty and how to rethink prosperity beyond materialism and consumerism.