Main menu

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Journey

- World Peace

- Stopping Racism in America

- Empowerment of Women

- More Principles...

- Prayer for America

Building a United Community: the Covenant

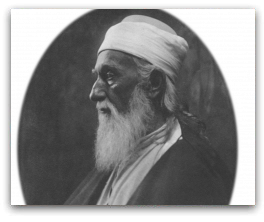

In a will and testament written by His own hand, Bahá’u’lláh explicitly named ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as the leader of the Bahá’í community and the interpreter of its sacred texts. Because of this covenant, which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá called “the most great characteristic of the revelation of Bahá’u’lláh” and “a specific teaching not given by any of the Prophets of the past,” the Bahá’í Faith has been spared the kinds of schisms that have shattered other religious communities.

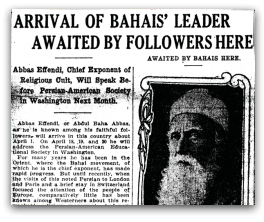

The first mention of the Bahá’í Faith in America occurred at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. One year later, the first American converts to the new faith began to appear. By 1905, there were enough American believers that a group of 422 signed and sent a letter which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá describes as follows:

They had covenanted together, so they wrote, to remain at one in all things, and the signatories one and all had pledged themselves to make sacrifices in the pathway of the love of God, thus to achieve eternal life. At the very moment when this letter was read, together with the signatures at its close, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá experienced a joy so vehement that no pen can describe it, and thanked God that friends have been raised up in that country who will live together in perfect harmony, in the best of fellowship, in full agreement, closely knit, united in their efforts.

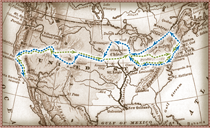

It was for the unity of the fledgeling Bahá’í community that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá expended so much effort, traveling to the Western world in advancing age and poor health, and emphasizing the importance of Bahá’u’lláh’s Covenant, without which the Bahá’í Faith surely would have experienced the divisive schisms that have eventually overtaken other movements of all kinds.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained:

Inasmuch as there was no appointed explainer of the Book of Christ, everyone made the claim to authority, saying “This is the true pathway and others are not.” To ward off such dissensions as these and prevent any person from creating a division or sect the Blessed Perfection, Bahá’u’lláh, appointed a central authoritative Personage, declaring Him to be the expounder of the Book.

While all Bahá’ís are encouraged to read the writings of Bahá’u’lláh and come to their own understandings of their meaning, only the interpretations of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá are considered an authoritative expression of Bahá’u’lláh’s purpose.

Attacks against ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

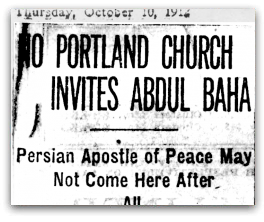

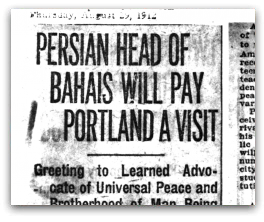

There were a few people among the early Bahá’ís who did not want to turn to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, who craved leadership or authority, and who tried to rally others to form new Bahá’í groups without the influence of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Among them were several well-known and influential figures, including the other sons of Bahá’u’lláh and the man who taught most of the early American Bahá’ís about the Faith. While ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was in America, they exerted great effort to stir up controversies among the Bahá’ís, and even attacked ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in the public press. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá largely ignored these attacks, while continuing to remind the Bahá’ís about the importance of the Covenant.Announcing the Covenant

‘Abdu’l-Bahá chose the city of New York to emphasize His station as the Center of the Covenant. On June 19, 1912, the newly translated Tablet of the Branch, in which Bahá’u’lláh expounds upon ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s station, was read to a gathering of Bahá’ís, after which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke about the implications of the Covenant. By all accounts this was a momentous gathering, so much so that on that day ‘Abdu’l-Bahá named New York “The City of the Covenant.”

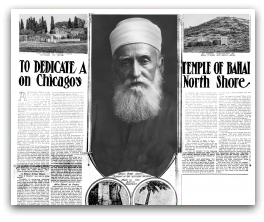

Building the Temple

Three years before ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s journey to America, a group of Bahá’ís formed the “Bahá’í Temple Unity” with the purpose of building the first Bahá’í House of Worship in the Western world. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá laid the cornerstone for that building in Wilmette on May 1, 1912; and as it was slowly being built on the shores of Lake Michigan, the Bahá’í system of administration was also being built around the world. Bahá’u’lláh had envisioned administrative institutions in every community:

Under the guidance of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, these began to take shape at the local and national level. In America, the “Executive Committee” of the Bahá’í Temple Unity started taking on more administrative functions, until by the time of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s passing in 1921, it was effectively functioning as the coordinating body for the United States and Canada. A few years later, under the guidance of Shoghi Effendi, it was replaced by a National Spiritual Assembly.It behoveth them to be the trusted ones of the Merciful among men and to regard themselves as the guardians appointed of God for all that dwell on earth. It is incumbent upon them to take counsel together and to have regard for the interests of the servants of God, for His sake, even as they regard their own interests, and to choose that which is meet and seemly.

Extension of the Covenant

The Bahá’í Covenant did not end with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. In his own will and testament, again written by his own hand, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá clarified the system of administration envisioned in the writings of Bahá’u’lláh, naming his grandson Shoghi Effendi as its authoritative interpreter and explaining the requirements and functions of the Universal House of Justice, the elected body that now heads the Faith.

This clear covenant has enabled the development of a worldwide community noted for both unity and diversity, in which individual understandings and ideas contribute to the collective understanding without ever threatening to tear it apart. Even though a few people have opposed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the Bahá’í administrative system, the worldwide Bahá’í community has remained undisturbed by their efforts to undermine its unity.

Today, you will find ordinary Bahá’ís around the world working as members of the elected institutions envisioned by Bahá’u’lláh, not as a career but simply as a service to the community. These institutions coordinate the community’s efforts to translate Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings into reality and action.