Main menu

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Journey

- World Peace

- Stopping Racism in America

- Empowerment of Women

- More Principles...

- Prayer for America

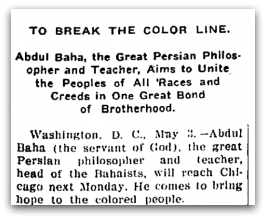

Stopping Racism in America

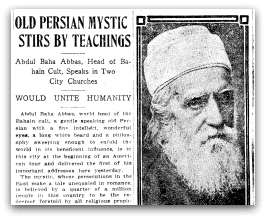

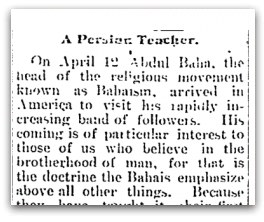

In 1912, the country was torn with racial division, and “separate but equal” was the highest level of interracial relations to which the nation aspired. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá challenged America to go beyond tolerance, to embrace diversity completely, and to demolish racial barriers in law, education and even marriage.

America in 1912, nearly 50 years after the Emancipation Proclamation that freed every slave, was decades away from realizing ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s vision of racial equality. African-Americans, although now freed from oppressive slavery, were universally regarded as lesser than whites. The so-called “Jim Crow” segregation laws had gained impetus from an 1875 Supreme Court ruling that the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution did not protect any Black person from discrimination by private businesses and individuals, but only from discrimination by states. So a racial caste system existed in the United States, reinforced from the pulpits of America’s churches, and pronounced as evident truth by scientists, phrenologists, and Social Darwinists, all claiming that persons of color were innately inferior both intellectually and culturally to whites.

In every state of the former Confederacy, the system of legalized segregation and disfranchisement was fully in place by 1910. This system of white supremacy cut across class boundaries and re-enforced a cult of “whiteness” that had predated the Civil War. These Jim Crow rules and norms, to name only a few, denied Blacks and Whites the right to dine together without a partition between them, condemned a Black male for offering his hand first to shake that of a White male, and denied the right of Blacks to show affection to each other in public because this supposedly offended Whites. These rules of “Jim Crow etiquette” operated in conjunction with Jim Crow laws—laws that excluded Blacks from public transport and facilities, jobs, and neighborhoods. These laws were largely entrenched across the South until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

But ‘Abdu’l-Bahá repeated his theme of racial equality throughout 1912, declaring that differences of race were not only natural, but laudable—to be celebrated.

“… difference of race and color is like the variegated beauty of flowers in a garden. If you enter a garden, you will see yellow, white, blue, red flowers in profusion and beauty — each radiant within itself and although different from the others, lending its own charm to them. Racial difference in the human kingdom is similar. If all the flowers in a garden were of the same color, the effect would be monotonous and wearying to the eye.”

The Bahá’í community: Striving for Interracial Harmony

Although the Bahá’ís held separate meetings in the first half of the 20th century, this practice over time disappeared as the Bahá’í community matured. Louis Gregory wrote to W.E.B. Dubois in the 1930s, stating that the new religion was the means of transforming hearts and erasing racism. “Were the Bahá’í Faith merely a cult with a human origin, it could attract only people who shared its views. Its mysterious Power is indicated by its ability to transform people whose views are diametrically opposed to its ideals and to give them new minds and new hearts.”

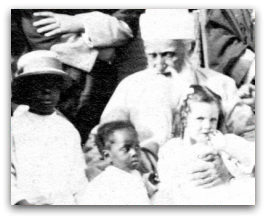

‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged interracial marriage as a way to unite the races quite literally, saying that such marriages would produce strong and beautiful offspring, children who are both clever and resourceful. In 1914, the first interracial Bahá’í marriage took place.

Bahá’ís of all skin tones were active in Civil Rights work throughout the 20th century and continue these efforts to this day, under the banner of one God, one human race, 100 years after ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to America.

Talk at Howard University

In a talk addressed to the students of Howard University, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stated unequivocally that skin color was of no importance before God, except as an adornment and a source of charm. Only among humans, He emphasized, had skin color become a cause of discord.

“The world of humanity, too, is like a garden, and humankind are like the many-colored flowers. Therefore, different colors constitute an adornment.

“Animals, despite the fact that they lack reason and understanding, do not make colors the cause of conflict. Why should man, who has reason, create conflict? This is wholly unworthy of him.”

Beyond Tolerance : Unity in Diversity

In this same talk, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá praised the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 as paving the way for universal and worldwide emancipation of persons of color, and emphasized the even higher goal for which this nation must strive, that of love, unity and complete integration between the races. This theme was one He returned to again and again. For example, in His talk at Hull House in Chicago, He said:

“Bahá’u’lláh has proclaimed the oneness of the world of humanity. He has caused various nations and divergent creeds to unite. He has declared that difference of race and color is like the variegated beauty of flowers in a garden. If you enter a garden, you will see yellow, white, blue, red flowers in profusion and beauty — each radiant within itself and although different from the others, lending its own charm to them. Racial difference in the human kingdom is similar. If all the flowers in a garden were of the same color, the effect would be monotonous and wearying to the eye.

“Therefore, Bahá’u’lláh hath said that the various races of humankind lend a composite harmony and beauty of color to the whole. Let all associate, therefore, in this great human garden even as flowers grow and blend together side by side without discord or disagreement between them.”

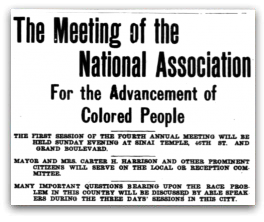

Race Amity Conferences

It was a woman, Mrs. Agnes Parsons, a prominent Washington D.C. socialite, who was tasked with planning America’s first Race Amity Conference in 1921. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told Mrs. Parsons in 1920 on her visit to the Bahá’í Holy Places in Haifa, Israel, that she must organize a convention in her city to unite the races. This admonition followed closely on the heels of widespread racial tension across the country, called the “Red Summer” of 1919. During July 1919, white servicemen returned from the war fronts and attacked Blacks. It turned into race warfare in Washington, D.C. when white gangs attempted to burn the black district, prompting its residents to arise to defend themselves and their property. It was into this environment, and against the separatism of Marcus Garvey, that Mrs. Parsons and Louis Gregory were thrust forth by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to plan an event that advanced the principle of racial equality, and that aimed at expanding the nation’s thinking to embrace not merely tolerance, but racial harmony and amity. Four Race Amity conferences were held between 1921 and 1924, an historic achievement by American Bahá’ís.

Read about one Bahá’í family’s experience of the collapse of segregation in the U.S.

As ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said in 1912:“[In the future] mankind will be as one nation, one race and kind — as waves of one ocean. Although these waves may differ in form and shape, they are waves of the same sea. Flowers may be variegated in colors, but they are all flowers of one garden. Trees differ though they grow in the same orchard. All are nourished and quickened into life by the bounty of the same rain, all grow and develop by the heat and light of the one sun, all are refreshed and exhilarated by the same breeze that they may bring forth varied fruits. This is according to the creative wisdom. If all trees bore the same kind of fruit, it would cease to be delicious. In their never-ending variety man finds enjoyment instead of monotony.”

Talks and Stories

- ‹‹

- 4 of 4