Main menu

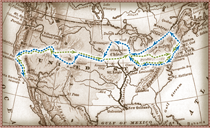

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Journey

- World Peace

- Stopping Racism in America

- Empowerment of Women

- More Principles...

- Prayer for America

Can There Be a Universal Religion

THE WORLD’S WORK

VOLUME XXIV

MAR to OCTOBER, 1912

A HISTORY OF OUR TIME

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1912

Copyright, 1912, by Doubleday, Page & Co. All rights reserved.

THE WORLD’S WORK

JULY, 1912

VOLUME XXIV

NUMBER 3

THE MARCH OF EVENTS

THERE are several ragged and ugly political things that ought to be forever condemned at this year’s election.

One of them is the disgraceful use of money even in primary campaigns. The publicity that a national law and some state laws now require has so far been only partly successful. A bought primary is a double crime.

Another is the old scandal of Republican patronage in the Southern States. Until the party rid itself of the disgrace of Southern delegates to its national conventions (bought by money, or by patronage, or by promises), the party and Southern political character will continue to degrade our national life. The subject smells to heaven.

Another is the degradation of the Presidential office such as we have witnessed at the hands of a President and of a former President. There ought to be a way whereby the conscience and the self-respect of the nation may be unmistakably heard this year in condemnation of these things.

All these are bad methods — degrading methods. There are also two large subjects of national policy — two big principles — that the election ought to throw some decisive light on. No large question of principle had a fair hearing during the period of personal noise that preceded the conventions.

The most pressing big subject, of course, is the tariff. At the last Congressional election the people voted unmistakably for a downward revision. They have not yet got it. Another such vote is necessary. If this subject be obscured at the election by personal and mere party wrangles, we shall make little real progress by this year’s contest. In fact, personal wrangling has so far played a hinderingly conspicuous part in the campaign to the loss of sober thinking and sane action.

The other great principle that the voice of the nation ought to be heard on is the governmental relation to business, especially to banking and the currency; but there seems small chance that this will happen. If the people at the coming general election, at which incidentally we choose a President, should give a decisive command about the tariff and about the Government’s relation to business, we should be paid for all the trouble and interruption of the summer.

[text missing] their personal reminiscences of those men and those times.

Here Mr. Hyatt found the solution of his problem. He went back to his office in Sacramento and wrote “A Calaveras Evening,” a pamphlet in which he told, in simple, vivid style, of the modern appearance of the old mining camp, and related the tales about the authors as they were told to him by the pioneers. With this narrative he reprinted the “Jumping Frog” and “The Luck of Roaring Camp.” Then he distributed the pamphlet to the teachers of the state, with the suggestion that it might serve as an example of a method by which instruction in English may be made vital and real to unresponsive students, for it brings a subject that often seems very far away right down to their doors, relating literature to a life they understand and appreciate. The pamphlet has been in great demand, has been circulated by thousands of copies. It has been so useful that Mr. Hyatt recently caused another pamphlet, of similar design, to be prepared, describing two other famous Californian authors, John Swett, the founder of the state’s public school system, and John Muir, the naturalist.

Here is a field for the ingenuity of educators. Such official publications as these of Mr. Hyatt’s are an inspiration to new endeavor and are of enduring usefulness.

CAN THERE BE A UNIVERSAL RELIGION

WHAT is Bahá’ísm? And who is ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the Persian, whose kind old face has smiled through its wrinkles out of all the newspapers of late? Is it another freak religion? Is he another fakir who served to centre the interest of idle women for a few weeks?

Perhaps rather more than that. The kindly old gentleman seeks seclusion rather than advertising, and when he has talked, he has said so few “queer” things — if any — in a vocabulary so free from occult terms, said so many wise and sensible things in so simple and yet somehow so impressive a way, that it is clear he is not of the type of Oriental mystic who has been in the habit of visiting us. His followers dimly hint that he is a reincarnation of all the prophets, but he smiles and waves it all away, and says: “No! No! No! I am not a prophet. I am only a servant of God. You also must be a servant of God.”

His religion, if he can be said to have a religion, is this: that all religions are at bottom one. The divine voice, he teaches, can and does speak as well through one creed as through another. The Christian should continue in his faith; the Buddhist in his; the Sufi does not fail to find God in his mysticism, nor the Rationalist in his logic. Only, it behooves them all to seek to enlarge and spiritualize each his particular faith, to enter into its deeper meaning and so find unity with all other men. There are three million Bahá’ís already, but, while most of them are Mohammedans, because the teaching arose in Persia, it is not uncommon to find Jews, Zoroastrians, Christians, and Hindus meeting together, each sect learning a larger interpretation of its particular faith in the light of the all-inclusive spirit of Bahá’ísm. In London, where his visit excited very great interest, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke in the Protestant preacher, Campbell’s, chapel and the Anglican Archdeacon, Wilberforce’s church; and he held up the Bible as as good a guide as the Vedas or the Koran.

There is something arresting — as there is in every effort to draw men together — in the visit to the West of this wise man of the East, this lover of his race who seeks to promote better understanding among men by persuading them that their religions are really all one. If there is any fact of contemporaneous history evident, it is the fact that the nations and races are drawing together; civilization is breaking down the barriers; knowledge is showing how vitally the interests of all people of all lands are connected. But religion can scarcely be said to have been in the past a unifying force; it has rather estranged than united. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá says: “If a religion be the cause of hatred and disharmony, it would be better for it not to exist than to exist.” Yet it is a question how far a religion can surrender its distinctive character without ceasing to exist.